[Article] Meetings of Mushroom and Music: Ryuta Imafuku

2025.9.10 (Wed)

The festival’s key phrase for 2025 is “nameless leaf clings to the matsutake mushroom.”

Inspired by Matsuo Basho’s metaphorical haiku and expanding our ideas, the festival aims to think about our encounters and co-existence with the unknown and the unfamiliar, as well as to consider the possibilities that spread from such thoughts. In conjunction with this, we asked three writers to contribute articles about this key phrase. We hope these writings will spark your interest and act as alternative doors for experiencing the festival.

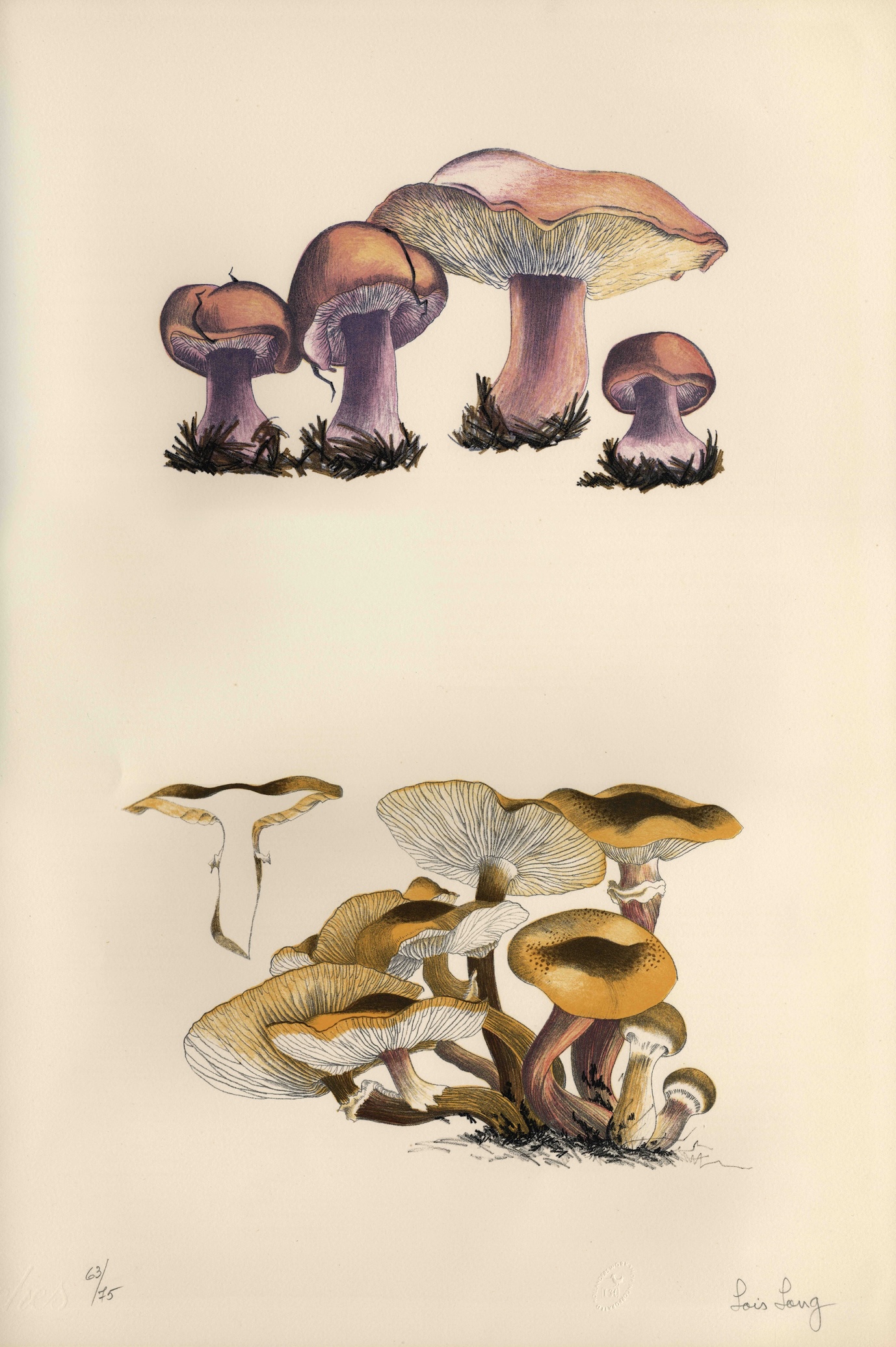

Fungi are mysterious life forms. These organisms, which include molds, mushrooms, yeasts, and (by broader definitions) slime molds, often defy scientific classification. Indeed, slime molds are neither plants nor animals, but cellular or plasmodial organisms with crawling amoeboid movements, and even predatory functions. Though familiar to us all, mushrooms mutate widely within the same species, secrete poison unpredictably, and are richly fascinating examples of chaotic life forms that deviate from our system of plant taxonomy. Taking an interest in this unorthodox life form of the biological world encourages the birth of a new sensibility that sloughs off the decadent conclusiveness and privilege of the human species, and attempts to enter the place where all the creations of natural world correspond, interact, and cross-pollinate.

The poet Kenji Miyazawa was involved in flowerbed design in the 1920s, and secretly conceived a socially transformative and bioethical project that would incorporate the wisdom found in nature into human life. The act of designing flowerbeds was not gardening to Miyazawa but what he called “landscaping.” Aiming to array new, synthesized landscapes with no distinction between the natural and humanmade, the project likened, according to Miyazawa, the act of rendering with flowers, trees, undergrowth, and moss to Beethoven’s Moonlight Sonata. It constituted an alternate means of arousing the cosmic order and higher bioethics of nature to which great music aspires. On the roots of the trees that Miyazawa was “landscaping,” various mushrooms emanated their chaotic life.

Miyazawa’s collection Spring and Asura (Third Collection) includes the following poem composed in May 1927.

Lo

Don’t kick

Don’t kick

What a thing!

Clear cochineal red

Dense white web of mycelium

There is nothing in this forest

with such vivid colors

Ah, muscarine

Lo!

Yank hard!

Really yank hard!

Atop the mountain, a cloud of ramune

A cool cloud of ramune bubbles forth

(Poem 1053)

This poem is about the fly agaric (Amanita muscaria), a bright red, highly poisonous mushroom that grows wild in the mountains and fields of Japan. Cochineal is a natural red pigment that we can get from scale insects, and here conveys the toxic-looking color of the fly agaric. Muscarine is a poisonous alkaloid found in the fly agaric. And yet, the reader detects not even a trace of horror in the lines of the poem; rather, at the end, Miyazawa gazes up placidly at the clouds bubbling up in the blue sky, likening them to ramune, a refreshing carbonated drink popular at the time. Warning us not to kick the mushroom, Miyazawa describes it elegantly as “clear” and “dense,” and calls out “Lo!” to the deadly poison. Before the fly agaric, or what we might regard as the quintessence of a chaotic life form, Miyazawa even seems to hum a prayer.

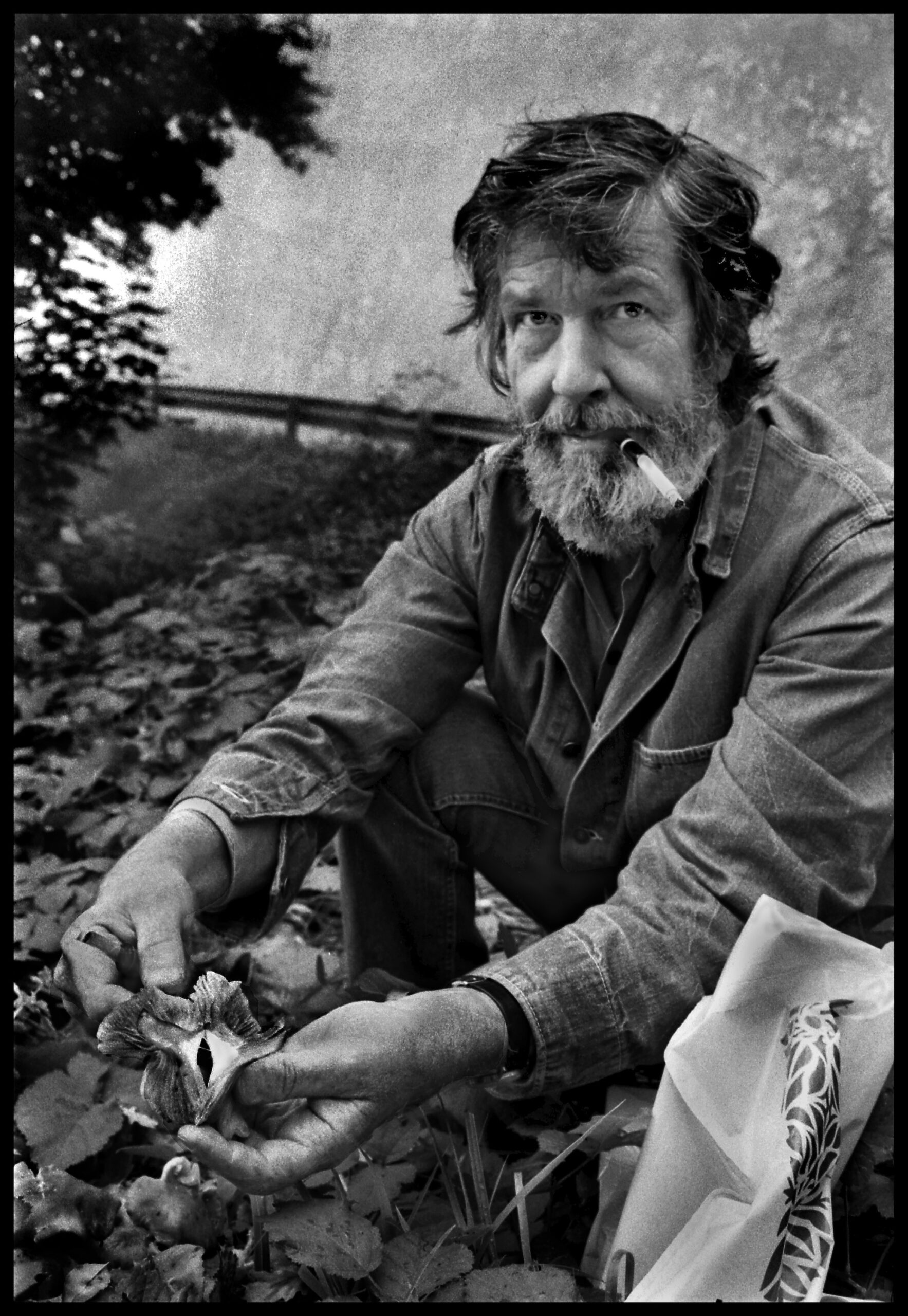

Another mushroom enthusiast was the composer John Cage, a mycologist the equal of any professional, so much so that he founded the New York Mycological Society. There is even a film that shows Cage mushroom hunting in the forests outside New York. As he ambles with wicker basket in hand, examining the roots of trees, he seems to be relishing the chance (a key concept in Cage’s music) that abounds in the mystery of the natural world and which we can experience through mushrooms.

The reason behind Cage’s interest in mushrooms is unimaginable for ordinary people. While flipping through a dictionary, he happened to find the word “mushroom” just above the word “music,” and was filled with inspiration. Cage immediately sensed a fundamental commonality between these two adjacent entries—chance. Both exist unimpeded, defying humanmade laws. In that regard, it was only natural that a composer would become a mycologist.

At a lecture he gave in the United States, Cage spoke about how chance manifests in mushrooms in relation to Japanese haiku. Both mushrooms and haiku are products of the seasons; both are deeply connected to the passage of time and sudden flashes of inspiration. Cage’s favorite haiku was one that Basho wrote shortly before his death.

Nameless leaf clings to the matsutake mushroom.

Cage discussed the meaning of the poem to the audience in English. He first recounted the scene literally described in the poem, that of the leaf from some unknown tree sticking to a matsutake mushroom. However, the somewhat banal and straightforward English translation of the poem by Reginald Blyth did not satisfy a certain Japanese composer that Cage knew (probably Toshi Ichiyanagi), who a few days later came back to Cage with the following new interpretation.

Mushroom does not know that leaf is sticking on it.

Cage was very taken with this version. He realized that the descriptions in haiku, though initially appearing to be just matter-of-fact observations of nature, are free and open, allowing for countless interpretations. And he felt intuitively that this embodied the very freedom of mushrooms. From this came an avant-garde, Cagian interpretation (a kind of hypertranslation!) of Basho’s haiku.

That that’s unknown brings

mushroom and leaf together.

In this interpretation, employing as it does the abstract “unknown” for the subject, the laws of nature are a scene of chance encounter. Cage was now enthralled by this process and eventually arrived at his ultimate interpretation of the poem, which he also shared at the lecture.

What leaf? What mushroom?

To which the audience erupted into laughter.

Listening to the audio recording of the lecture, I smiled at Cage’s impromptu and profound wit, and thought of the provocateur and rebel that is chance contained in the taste of the mushrooms we eat every day. I must go to the forest, not the supermarket. I will come across mushrooms covered with fallen leaves, wood chips, and moss, collect the evidence of this symbiosis in a basket, lightly fry them with a sprinkle of salt, and bring this “chance” to my mouth. I risk my life to play with chance, fully accepting the fear that I may be in danger. It is an adventure of the tongue replete with inimitable joy.

Reference

The Complete Works of Kenji Miyazawa (New Edition) Vol. 4: Poems 3, Chikuma Shobo, 1995

Author Profile

Ryuta Imafuku

A cultural anthropologist and critic, Ryuta Imafuku’s research focuses on creole cultures in the Caribbean, Mexico, and Brazil. He is the head of Amami Free University, an outdoor school that links the archipelagos of Amami, Okinawa, and Taiwan. Armed with a sanshin Okinawan instrument, he explores the possibilities of the modern minstrel. He has taught at the Pontifical Catholic University of São Paulo and Tamkang University in Taiwan. Imafuku’s many publications include The Archipelago-World, Henry Thoreau: The Wild School of Unlearning (Yomiuri Prize for Literature), and Kenji Miyazawa: The Wisdom of a Good-for-Nothing (Kenji Miyazawa Prize, Kadokawa Culture Promotion Foundation Prize). His most recent book is Thoughts on Masks.