【コラム】感じの良い声とは? ——「モシモシ」から振り返る、声とジェンダーの歴史 (石井香江)

2021.10.12 (Tue)

“もしもし?!”

新型コロナウイルス感染症拡大の影響で、オンラインでの対話などにより目の前には存在しない、不在の身体に呼びかけることが多くなった。いまここにいる/いない他者の声や、いま起きている/起きていない音にいかに耳を傾けるのか、これまで以上に問われているのではないでしょうか。「もしもし」と呼びかける主体はわたしなのか、それともわたしは呼びかけられているのか。そして、見えない「もしもし」の向こうをいかに想像していくのか。ここでは、今回のキーワード“もしもし?!”を出発点に、さまざまな視点からのコラムを展開します。

コロナ禍の中でTeamsやZoomなどのWeb会議ツールが広く活用され、遠隔地間でも顔を見ながらの会議や授業が可能になっているが、カメラをオフにして参加する人も少なくはない。対面であれば相手の身振りや顔の表情から、感情の動きや理解の度合いを確認できるが、顔が見えない場合、聞こえてくる声がすべてである。その分、聴覚も敏感になる。伝えられる情報そのものだけではなく、伝える際の話し方、音量、抑揚やテンポに表れる「声の表情」に、意思疎通の良し悪しが大きく左右されることにあらためて気づかされる。

現在、コールセンターや電話代行サービスなど接客の現場では、聞き取りやすい声を出す技術的なボイストレーニングの域を超えて、「声の表情」を良くする指導も行われている。相手への配慮、丁寧さや機転が、声に「表情」を与えるという理解が基礎になっている。これは裏を返せば、いかなる声も訓練によって変化しうるということだが、聞き取りやすく、感じの良い声の持ち主=女性=電話交換手という本質主義的な見方が長い間存在していた。

電話をかけた相手とそのまま通話するのは今でこそ当たり前だが、電話が自動化されるまでは、欧米でも日本でも電話交換手が電話を繋いでいた。その際、電話交換手は「もしもし」と応答したので、日本では「モシモシ嬢」、英語圏ではHello Girlsとも呼ばれた。主にミドルクラスの女性に切り拓かれた新しい職業であったので、現在でもテレフォンオペレーターは女性職というイメージが根強いが、創成期には男性が担っていた。しかしその後、徐々に女性に切り替わっていったのはなぜなのか。女性が男性よりも電話交換手に適している理由としてよく挙げられたのが女性の声だった。19世紀末から20世紀初頭のドイツ帝国議会でも、交換手として女性を採用することに反対する議員に対し、逓信省次官は女性の声の高さと、聞き取りやすさ・感じ良さとを結びつけ、女性の「適性」を強調した。しかし、ここには論理の飛躍がある。聞き取りやすい声が、感じ良いものとして聞こえるとは限らない。

この時期にベルリンで幼年時代を過ごしていた思想家W・ベンヤミンは、初期の電話の技術的問題と、それに起因する利用者の苦情処理にあたった電話局と電話交換手について伝えている。技術的問題で電話がなかなか繋がらない事態が当時頻発していたが、利用者の怒りの矛先はまずは電話交換手に、その後電話局に向けられた。当時の利用者の多くが社会階層の高い男性であったことを考えると、最初の段階で利用者の怒りを極力抑えるにはどうしたら良いのか。同時代の日本でも、男性の電話交換手は売り言葉に買い言葉で、利用者と喧嘩になると報告されている。そこで、容易には激さず、しかも、利用者が怒りをぶつけることをためらう対象として白羽の矢が当たったのが、育ちの良い未婚の娘たちだった。「感じの良い」声とは実のところ、高い社会階層の女性たちに期待された話し方や態度と、嫁入り前の娘たちに対する利用者の期待などの諸々から生み出されたアマルガムであった。

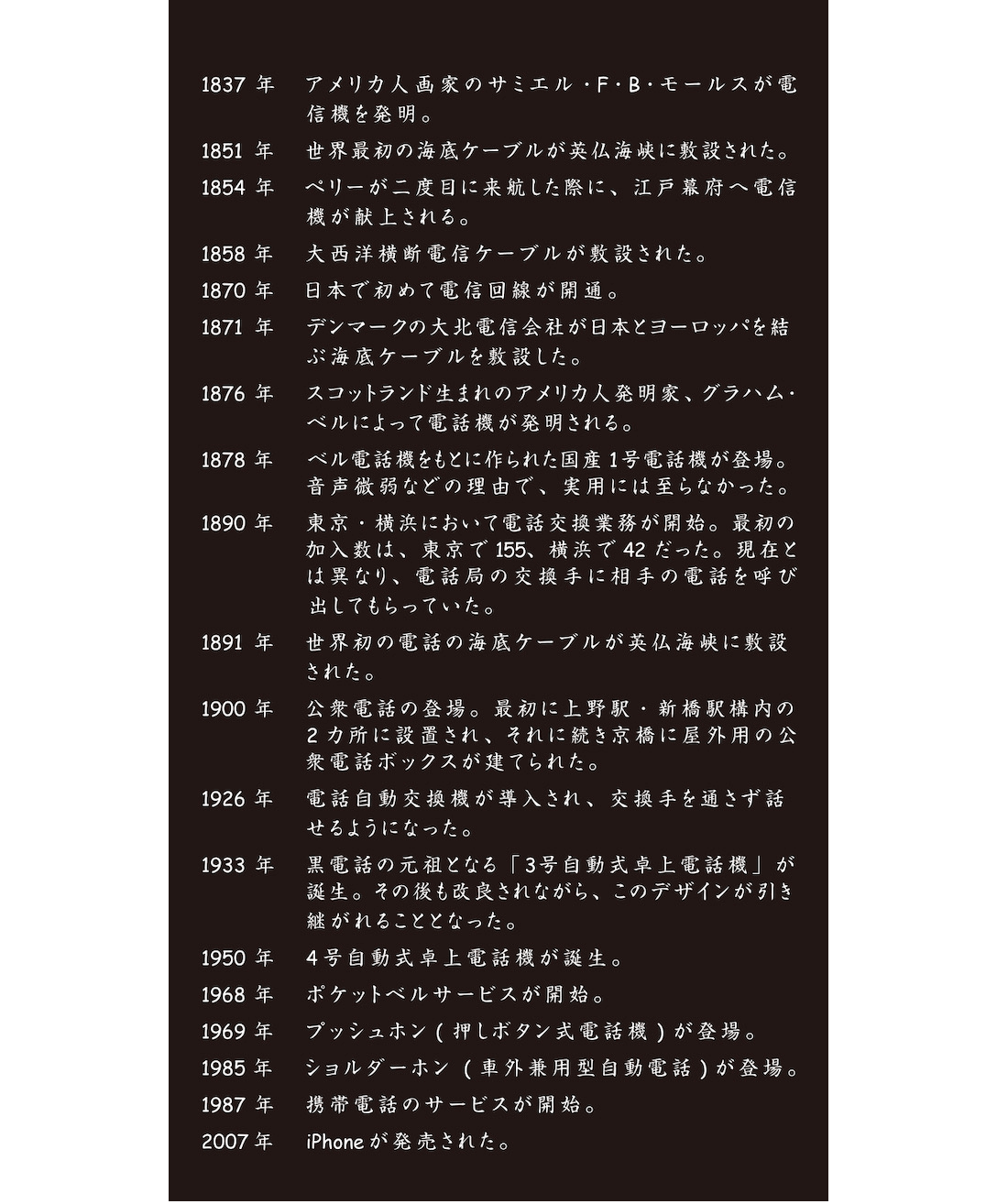

☝️電信・電話の歴史

年表監修・解説:石井香江

参考URL:NTT技術史料館

http://www.hct.ecl.ntt.co.jp/index.html

日本で電話が生まれて150年。黒電話や公衆電話など『電話の歴史』を振り返る。

https://time-space.kddi.com/it-technology/20191023/2765

☎️歴史解説☎️

遠くへと情報を伝えるために、人類は知恵を絞って工夫を重ねてきた。太鼓の音、狼煙、烽火、鐘、号砲、手旗信号、伝書鳩や腕木式通信など、信号や言葉を遠隔地に伝えるあらゆる方法が考案された。とりわけ19世紀以降の工業化と帝国主義化の進展により、情報通信技術は著しく発達した。電気を利用した通信形態である電信、続く電話の登場を機に、情報が信号や声として瞬時に遠方に届けられるようになった。鉄道網の拡大、スエズ運河の開通や汽船航路の整備に加え、大西洋を横断する電信用の海底ケーブルが敷設されることで、人・モノ・情報の移動は加速化し、「世界の一体化」に拍車がかかった。

モールス信号を送受信する電信は、西南戦争や義和団事件のように戦局を有利に展開しようとする権力者に利用されただけでない。世界のニュースを迅速に伝えて経済活動を促し、各地域の民族意識も刺激した。一方、電話はリアルな肉声を伝えるという点で革新的であり、日常的なコミュニケーション手段としてより身近な存在となった。20 世紀末以降、携帯電話やスマートフォンなど情報端末機器の未曽有の発達と普及で、声だけではなく文字や絵、映像までも送受信することが可能となり、時間と空間の圧縮は一層進展している。

石井香江

同志社大学グローバル地域文化学部准教授。社会史・ジェンダー史研究者。近現代の特にドイツと日本の労働のジェンダー化に注目した研究を行っている。著書に『電話交換手はなぜ「女の仕事」になったのか:技術とジェンダーの日独比較社会史』